Toku remembers the first time he carved his own variation on one of Sixten's well-known shapes: the famous cross-cut design, now better-known as the blowfish. The Ivarsson model insists that the line of cross-grain running down the shank and around the bowl must be centered and continuous. Ever the improviser, Toku began imagining what would happen if he made this line more flexible. In 1980, he carved his first variation on the Sixten cross-cut – the first Tokutomi blowfish. But the response from the Japanese market was negative and Toku abandoned the design. (The pipe-smokers who disliked Toku's work had been taught that the "the best pipes in the world" were made by the Danes. Since Toku's shapes didn't look like the pipes they had learned to admire, they were not ready to accept their fellow countryman's work.)

|

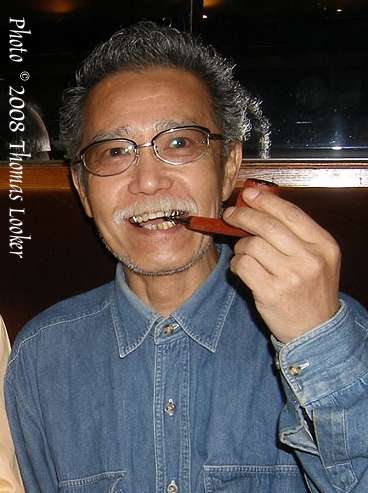

WHAT'S IN A LINE: An Ivarsson-like cross-cut (lower pipe) from 2002 and one of Toku's famous flexible form "blowfish" from 2005 show the huge differences in shape that become possible when you allow the pipes center-line to curve, however slightly. The diagram below shows the subtle "wiggle" that Toku adds to the bottom of the 2005 pipe. But how much more fluid and clay-like does the rest of the pipe become, thanks to this small adjustment! |

After he married his wife, Kazue, in 1983 and they had their only child, Yuki, in 1986, Toku struggled to support his family by making the familiar Danish shapes his customers wanted. But by 1992, he realized he could not earn enough money with his pipes, so he reluctantly scaled back his briar dreams, moved to Maebashi, and took a job in a small iron workshop owned by his brother-in-law.

Toku now had time to make only about ten pipes a year. He felt his creativity being stifled. The passionate aspirations that had inspired him while standing in front of Ko'un sculptures or while walking along the canals of Copenhagen had been dimmed and depleted by two decades of disappointment.

Then Toku's life took an unexpected and potentially tragic turn. In 1995, at the age of 47, he was diagnosed with stomach cancer. After a major operation and a long recuperation, he was pronounced entirely free of the disease. But the removal of his stomach had permanently altered his physical condition. He could no longer continue as an iron worker.

While Toku was in the hospital, his wife, Kazue, brought him some of his old art books. Since fate was forcing him to "start his life over again," Toku began hoping he'd been given a second chance to build a career out of making beautiful things. One of the books he looked through included pictures of the traditional Japanese craft of Netsuke, small objects carved out of ivory. Toku had always loved this art form; now he found himself so moved that he said to himself, "If I'm still alive at the end of all this, I'll learn Netsuke!"

A few months later, Toku began training as an ivory carver, studying with one of the masters of the craft, Kobari. Over the next few years, Toku's skills grew. Several of his pieces were exhibited in museums.

|

To thank businessman Barney Suzuki for helping him enter upon his new life in briar, Toku made this ivory and boxwood pipe in 2005, two years after he stopped producing ivory pieces for sale. (The shank is wood that's shaped to look like bamboo.) This beautiful and touching "ivory celebration of briar" is the last carving that Toku has made in that material. |

Though Toku obviously preferred carving ivory to being an iron worker, he did not experience the intense satisfaction, the joy of creation, that came to him when working with briar. Not only did the milky-white material afford a more muted palette of color and texture than wood, but the many the rules and traditions surrounding the Japanese ivory craft also constrained Toku.

It seems to me that the explosion of creative energy in Toku's pipe carvings over the past five years represents, in part, a passionate response to six years of discipline as an ivory carver and his earlier frustrations in the iron factory. Toku's imagination had been inhibited first by iron then by ivory. Briar remained for Toku the only path to creative emancipation.

He was not able to free his spirit entirely by himself; Toku needed the help of two pipe connoisseurs, from different generations and different countries. In 2002, Barney Suzuki, a 64-year-old businessman, historian and elder-statesman of the Japanese pipe community, met a 21-year old American entrepreneur, Sykes Wilford, owner of Smokingpipes.com. Sykes had come to Japan looking for local pipe carvers whose work might interest American pipe-smokers. Barney introduced Sykes to Toku and his work. The young American had an interest in art history and was unusually sensitive to the aesthetic potential of briar pipes. He found himself "completely blown away" by what Toku showed him. Sykes recognized immediately that here was a carver who combined the technical virtuosity of the finest Danish Carvers with an entirely new and exciting sense of design.

Toku started making a few pipes for Sykes to sell on Smokingpipes.com. Cautiously, the pipemaker started to introduce some of his more expressive, asymmetrical shapes, and when Sykes lavished praise on one of Toku's "un-Sixtenish" blowfish shapes, Toku finally understood that his creative landscape had completely altered. At long last he had discovered an audience that appreciated (and bought!) his work. He was free to improvise, to play, to invent – to follow the dictates of his own inspiration. Within a year of meeting Sykes, Toku stopped carving ivory and, at the age of 55, became the kind of pipemaker he had always dreamed of being.

The development of Toku's work since 2003 has dazzled everyone. At first, Toku improvised variations on certain familiar Danish shapes, introducing subtle asymmetries, adding a "clay-like" feel to his shapes, and using plateau in distinctly un-European ways. (In most Japanese arts and crafts, irregularities in a natural object are not considered "flaws" to be eliminated; rather they are viewed as essential parts of the object's beauty.) Then Toku began developing brand new shapes which he pursued with increasing confidence and imaginative brilliance.

In the fall of 2004, Toku finally paid his return trip to Denmark, to exhibit some of his pipes at a Copenhagen show. The Danish and European carvers who saw Toku's pipes were astonished and delighted by his work, recognizing his unique talents.

But Toku had also journeyed to Copenhagen so he could fulfill his promise to Sixten Ivarsson to pay him a visit "when he had become a successful pipemaker." A few days after the show, wearing a coat and tie, Toku stood in the November rain in front of his mentor's grave, said a prayer in Japanese, and wept.

As impressive as was Toku's debut on the international pipe scene in 2004, nothing could have prepared the pipe smoking community for the explosion in his creativity in the following years. In 2005, his Cavaliers became bolder, bigger, and more overtly expressive of traditional Japanese lines and forms – from the angles of Samurai swords to the curves of clothing and body in Ko'un's female portraits. Throughout 2006 and 2007, blowfish and horn variations became larger and more complex as Toku added more lines of energy and flow to his already flexible sense of shape. Toku now seemed to have developed two distinct "modes" of carving, which I've thought of as "clay" and "stone" but which also seem expressive of two different Japanese traditions: an organic, rural culture of fluidity, ambiguity, and gentle elegance; a sharp, urban culture of angles, hard edges, and confident sophistication.

The final wonder of Toku's continuing exploration of briar is that as much as he may push and prod the outward forms of his compositions, the interior of each piece remains a smoking pipe – grounded on the engineering and design principles taught by Sixten Ivarsson.

Coda: Joy and Gratitude

November 2007