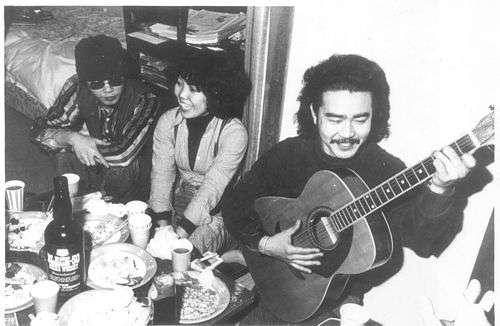

Toku with guitar and friends, 1970's

Hiroyuki Tokutomi has followed an unusual path to become one of the premier pipemakers today.

Born in 1948, to a family that included the writer and journalist Soho Tokutomi, Toku remembers that he always enjoyed drawing and making things out of wood. His father was an engineer who had piloted fighters during the war. His mother encouraged the young Toku's interest in art. After he finished school in the mid 1960s, Toku began studying Japanese painting and ceramics with the son of a well-known artist. He also played guitar in a jazz combo that had regular gigs in and around Tokyo. Most significantly, during this period Toku fell under the spell of two artists who would become the major inspirations in his creative life: a Japanese sculptor and a Danish pipemaker.

Toku used to spend his weekends visiting Tokyo art galleries and here, for the first time, he saw the work of a famous Japanese sculptor and teacher, Takamura Ko'un (1852-1934). Ko'un had developed a style of wood carving that mingled traditions of Japanese Buddhist sculpture with certain elements of European art (especially the work of Rodin) to create a remarkably vibrant, thoroughly Japanese form of composition. The young Toku found Ko'un's oeuvre revelatory and thought his portrayals of the female form were particularly beautiful and inspiring.

During my stay in Tokyo, Toku retraced his steps as a young man and took me to some of his favorite museums. He eagerly showed me works by Ko'un and I could sense that they still thrilled him. At one point, he caught sight of a statue that he had not seen before and I heard him catch his breath. It was sculpture depicting the Goddess of Mercy as a woman standing in a traditional Buddhist pose. While other similar statues in the museum seemed stiff and formal, Ko'un's Goddess exuded a palpable sense of life.

With growing excitement, Toku pointed out how Ko'un used graceful, pliant folds of clothing to reveal the curves of the woman's body within. He began moving his hands to evoke the forms he was seeing, and I noticed that his gestures were the same as those he uses when talking about the contours of one of his pipes. Then Toku told me that it was while looking at Ko'un statues like this, years ago, that he first realized what he wanted to do in his life: to make beautiful objects in wood that came as close as he could to Ko'un's artistry.

|

Sculptor Takamura Ko’un: Influence and Inspiration |

|

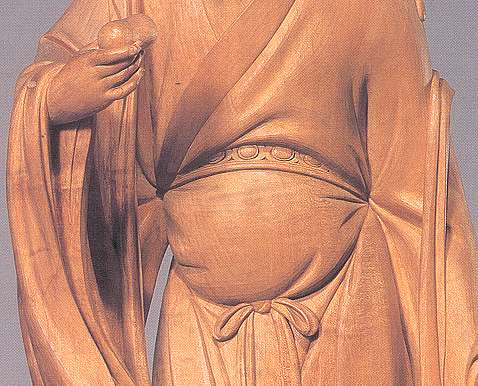

Goddess of Mercy by Takamura Ko’un (1852-1934): Sculptures like this moved the young Toku to dream about making beautiful objects out of wood. Today, Toku’s pipes often contain lines and shapes inspired by Ko’un’s work - for example, curves that echo Ko’un’s drapery and shapes that recall his soft, organic modeling. |

|

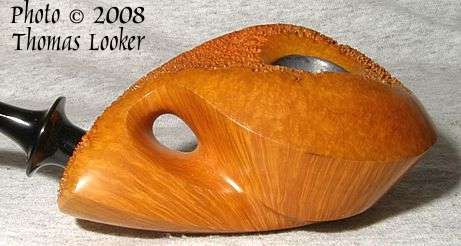

Horn Sitter, 2007: The carving contains several sources of inspiration: the fluid curves of Ko’un’s sculptures, traditional Japanese use of “implied space,” and Toku’s fascination with the Mobius strip. Toku melds these elements into a breathtakingly-beautiful composition. |

|

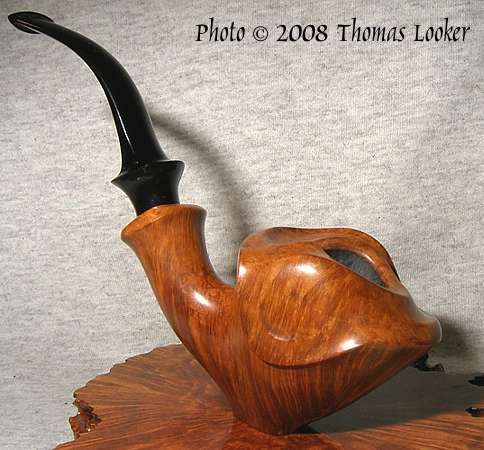

The Crab, 2007: This massive carving possesses an astonishing fluidity of line and form. In the broad swing of the wrap-around tail, you feel the same sense of swaying grace that’s present in Ko’un’s carvings of the human form. |

|

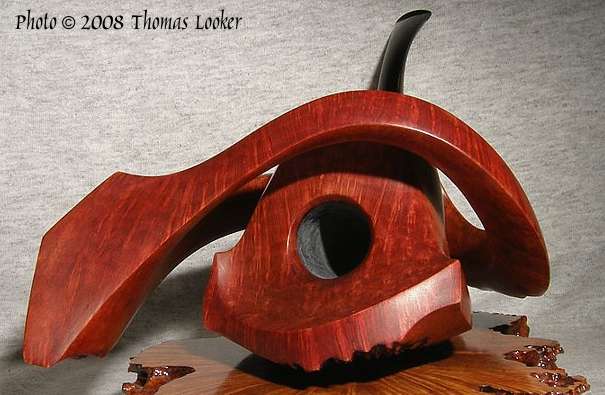

Bridged mushroom, 2006: This wonderfully organic composition exudes a fecund energy, fitting to any live mushroom. The way Toku has contoured the rounded surfaces reminds me of how Ko’un makes the cloth of a kimono swell above a woman’s belly. |

|

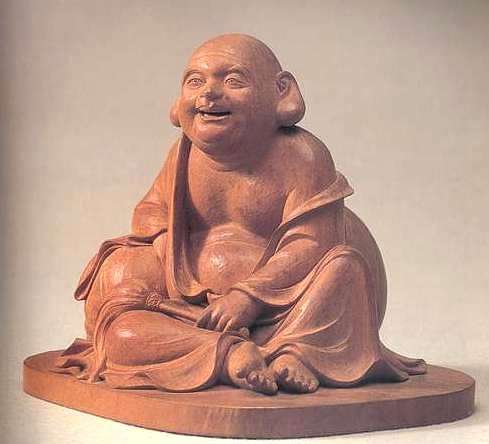

Sitting Monk by Takamura Ko’un (1852-1934): Toku’s carving also brings to my mind the plump, jolly forms of this Sitting Monk, in which feelings of emotional animation merge with a sense of physical rootedness. As if to underscore the resonance between the pipe and the sculpture, note that the monk appears to be wearing Toku’s briar mushroom on his ear ... |

|

|

|

While pursuing his art studies in the late 1960's, Toku also carved his first pipe, using a pre-bored ebauchon. After making a number of pipes, he won first prize in an amateur competition. Then in a Tokyo pipe store he saw for the first time the work of the Danish masters. As Toku explained, "I became enchanted with works by Sixten Ivarsson, Emil Chonowitsch [Jess's father], and [Jorn] Micke. I was especially taken with a freehand sitter Dublin by Sixten and a cross-grain pipe by Lars [Ivarsson]. It was then I started to dream about visiting them."

The more Toku worked with briar, the more fascinated he became with the

material. "Briar never shows its capability from the beginning," he says.

A carver never knows exactly what he will find when he starts revealing

the inner structure of a block. "Always it is a challenging material.

Carving briar can never be compared with carving or sculpturing ordinary

wood [where the grains are both more predictable and less visually

determining]."

By 1974, the young Toku had committed himself sufficiently to the

pipe-making craft to arrange a trip to Copenhagen so he could learn from

the masters he already revered. Toku traveled on his own, with a little

financial help from a Japanese pipe distributor, Haruyama.

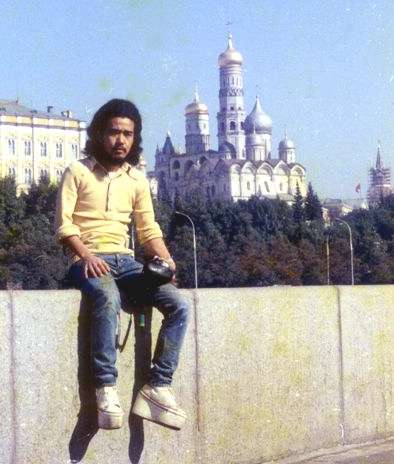

Toku in Moscow on his trip to Copenhagen in 1974.

Though Toku spoke neither English nor Danish, everyone he met in Denmark seemed to recognize the creative passion that was driving him. He stayed for three months, spending most of his time in the workshop of Sixten Ivarsson. At a symposium on Sixten at the Chicago Pipe Show in 2006, Toku described what it was like to spend a day in the great man's shop: "Sixten had many friends visiting him almost everyday, such as Emil Chonowitsch, collectors from the U.S., Mrs. [Bo] Nordh, and young ladies from neighboring shops and stores. Watching Sixten carve out a powerful and great pipe from a small briar block, I dreamed myself to do similar things in the future. Sixten is the one who gave life to smoking pipes. He made the pipe into an object of art, changing it from being just a simple smoking instrument."

Toku learned a tremendous amount about briar and about pipe-making from Sixten Ivarsson and today he traces many of his own techniques back to his mentor—everything from how to achieve the best possible shape from any briar block to how to shape the interior of a mouthpiece. (Before Sixten showed him how to create a fan-like opening inside the bit, Toku had drilled only a straight air-hole.)

Tokutomi traveled home to Japan with Sixten's parting words echoing in his mind. ("Come back and visit me again when you have become a successful pipemaker. But when you return, wear a jacket and tie.") For the next eighteen years, he worked hard to succeed as a pipemaker, first distributing his briars through Haruyama, then, in 1978, setting up a small workshop and selling directly to a few pipe shops. But the market for Toku's work was weak. Japanese pipe-smokers were uninterested in his attempts to innovate and explore new shapes and forms.

|

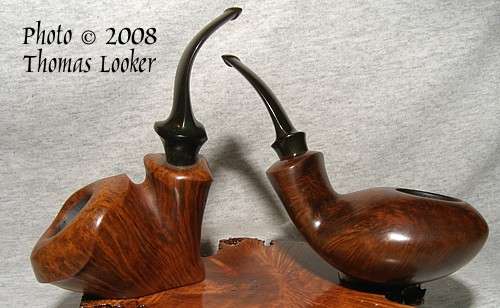

ABOVE: Two Toku pipes from the 1980's adhere closely to Sixten Ivarsson forms, while ... BELOW: This 2003 sitter shows some Toku variations on Danish themes (e.g. the extremely "floppy" rim) that did not impress Japanese pipe-smokers twenty years earlier. |

Navigation