|

On a quiet country street outside the city of Maebashi, Japan, near fields

that once grew mulberries for silk, I stand in the bright autumn sun and

listen to the random twitter of birds and the dry hum of wind blowing down

Mt. Akagi. The contemplative calm of this warm November day envelops me …

until, abruptly, the dull throb of an air-compressor breaks the stillness.

The noise is coming from the back of one of the long, low houses nearby.

Then the explosive rasp of a sanding disk on wood slices into the

landscape like a sword blade, silencing the birds and challenging the

wind. Hiroyuki Tokutomi has begun to make a new pipe.

Tokutomi's home and workshop lie within the historic Tone River valley on

the northwestern corner of the Kanto plain, 100 kilometers northwest of

Tokyo. Surrounded by a special mixture of natural and cultivated beauty

(mountain peaks and hot springs, flower gardens and temples) the small

city of Maebashi is proud of its traditions of commerce, culture, and the

arts stretching back several centuries. And though no silk industry

remains, one of its quieter citizens continues to make beautiful objects

that delight and astonish people around the world.

For, out of this unique landscape, a new vision for briar pipe design has

emerged and spread throughout the international community of pipemakers.

Hiroyuki Tokutomi's imagination has mixed the classic Danish principles of Sixten Ivarsson with his own distinct Japanese sensibilities, and, in the

process, developed what I'd call a "new aesthetic language" for pipe

carving. Tokutomi's unusual, startlingly-beautiful work has shaken up the

way many pipemakers look at briar and suggested new possibilities for

expression and exploration.

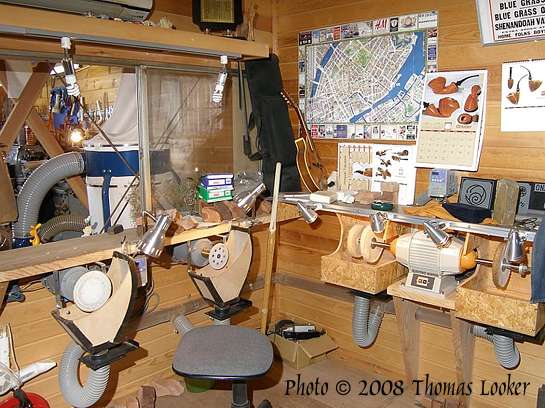

Built onto the back of his one-story house, Toku's studio is a large

rectangular room whose unstained wooden walls are decorated with

photographs, pipe calendars, a street map of Copenhagen, a poster for the

Grand Ole Opry radio program, and decorative ceramics. The familiar tools

of the pipe-making trade spread out comfortably between work tables, a

desk, and storage areas. In opposite corners stand his large lathe and big

blue sandblasting machine. Appropriately enough, Toku's two shaping disks

sit in the middle of the workshop, near two buffing and polishing disks.

All four wheels have special electronic controls that Toku has built

himself.

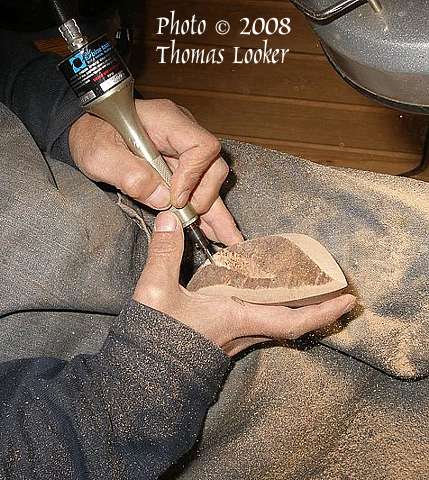

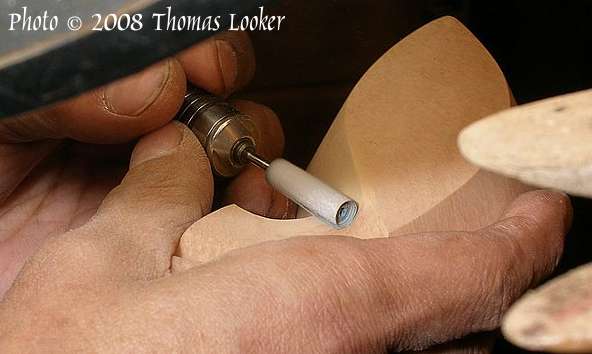

The most unusual tools in the shop play the most significant role in

Toku's pipe designs. Toku uses "air turbine" Dremels, high-speed

hand-drills powered by air pressure rather than electricity. The Dremels

hang from the ceiling above Toku's desk like a collection of dentist

drills. These air-powered tools have much more torque than those driven by

electricity; the extra power gives Toku's hands much greater control – and

his imagination much greater freedom – to mold briar into astonishing

shapes.

|

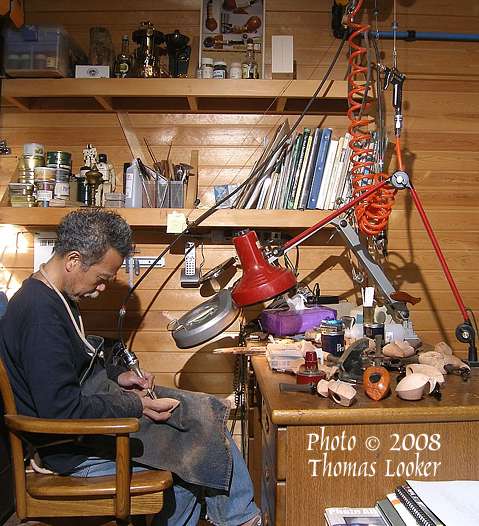

Toku as "dentist." (In fact, his very

first Dremel-like machine was an old dentist's drill.) |

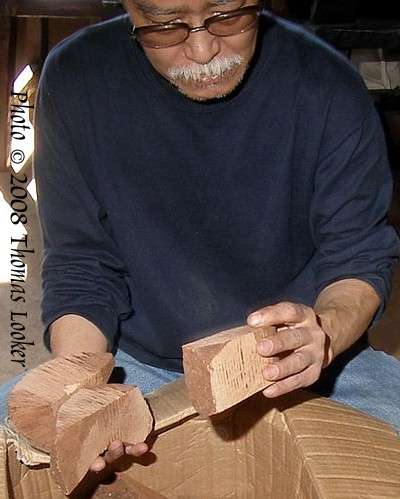

On the afternoon that I visit Toku, he is working on a large briar block

carefully chosen from the latest box of wood to arrive from the Italian

master cutter, Mimmo (Romeo Dominico) in Taggia, Italy. (Whenever anyone

asks Toku why he makes pipe shapes the way he does, the first answer is

always, "Mimmo's briar!" For his part, Mimmo loves preparing

unusually-shaped blocks for Toku, partly because he can never be sure what

shape Tokutomi will come up with.)

Toku has selected this particular block because he likes the way its rough

plateau will fall on the side of the "elongated blowfish" he sees in the

wood, rather than along the top or bottom. (Toku actually thinks of this

newest blowfish variation as a Salmon, with its long, sleek bowl and

thick, often "fluted" shank. Unfortunately the Japanese word for Salmon is Sā-ke, which non-Japanese speakers might confuse with the beverage, so

Toku has refrained from making the name official.)

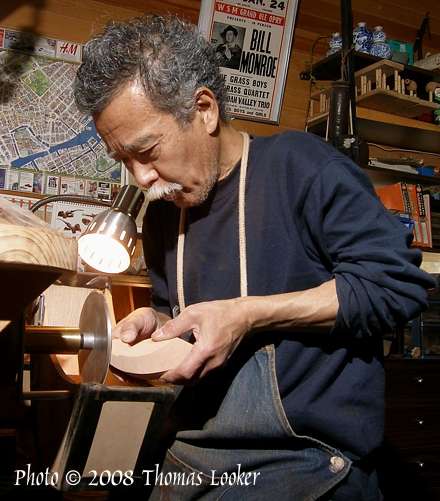

To see Toku shaping a pipe is to observe a master improviser at work. He

has few set patterns for his pipes, no rigid templates that he applies.

Occasionally he will draw pictures of pipes he'd like to make and he

usually has a general idea of the shape he sees in a particular block. But

once he sits down in front of the sanding wheel, conscious ideas tend to

evaporate. He becomes aware only of the briar in his hands: the twists and

turns of the emerging grain, the flow of the lines he is defining, the

feel of the forms beneath his fingers. Like a jazz musician who plays by

ear (and Toku has been a guitarist since his student days in the 1960's),

Toku's creativity is kinesthetic and experiential, rather than

intellectual and analytical.

Toku presses his briar block against the spinning sandpaper with a coiled,

athletic intensity. His feet are spread wide and his small body leans

forward on the edge of a stool as his hands guide the wood up and down,

back and forth, against the rough surface. The force that Toku applies and

the speed with which he moves suggest a wiry toughness and powerful

creative drive lurking within his thin frame, and his friendly, ingenuous

personality.

Toku alternates his periods of intense activity with moments of

concentrated reflection, during which he sits back on his stool and stares

fixedly at the wood. Sometimes he traces an invisible line with his finger

before resuming his work on the sanding disk.

|

"When I start making the bowl, I'm

already beginning to think about the shank. When I'm working on the

shank, I'm thinking about the mouthpiece. It all follows in

sequence." - H. Tokutomi |

Once Toku has shaped the block into a generally ovoid form he moves to a

smaller sanding wheel to clean up the plateau and shape some of the

tighter angles and surfaces. In this particular pipe, Toku has merged the

shank and bowl in a new way – the curves of the bowl flow directly into

the curves of the shank. From here on, his task will be to separate and

distinguish the two sections of the pipe from each other.

By the time Toku turns off both sanding disks (about 45 minutes after he's

started), the rough chunk of briar has been transformed into a smooth,

undulating form whose curves and contours already seem distinctively "Tokuish."

The underlying blowfish theme is apparent in the pattern of grain, as both

sides of the briar are splattered with birds-eye, while the circling edge

displays vivid cross-grain.

Central to his design will be a long, narrow space "in the middle" of the

shank, a bridge or ribbon of briar that will run from the rear of the

shank to the top of the bowl. This open area will help lighten the overall

composition. At the same time, the curved shapes of the ribbon will create

a sense of rippling movement, further evoked by its flowing grain, and

varying textures (the left side will contain a line of plateau).

Toku will use a Dremel to "excavate" the bridge and add contours to the

ribbon, but to get things started, he first moves to the familiar pipemaker's lathe. Precisely at a moment when many carvers would use their

lathes to drill length-wise into their blocks to make air-holes and

tobacco chambers, Toku sets up his machine to burrow a small hole across

the pipe, marking the spot from which the crucial curve of empty space

will grow.

Toku marks where he will drill the hole in

the shank.

|

Most of the time, Toku uses this lathe to

drill tobacco chambers, air-holes, and stems. |

Once Toku has completed his drilling, he moves to his old wooden desk. He

grabs one of his dangling Dremels and then sits down in a comfortable

arm-chair. He wraps sandpaper around an appropriately-sized bit, lowers

his head, and starts "digging."

Toku works with surprising speed. He knows exactly what he wants and is

extremely dexterous with the Dremel (which, by the way, he has specially

designed for his left hand). Toku quickly enlarges the hole, then, using a

smaller bit, he starts contouring its sides. Astonishingly, the more briar

Toku takes away, the softer become the lines and shapes of the remaining

wood. He makes a briar pipe look as though he had molded it out of clay,

and as his small hands manipulate the whirring Dremel, I know I am

witnessing part of that magical transfiguration. Yet how can a high-speed

"air-turbine" drill, that gouges out sprays of sawdust from hard,

beige-colored wood, create lines that seems to flow like water and shapes

that seem to move and grow like organic matter? To my eye, Toku's sorcery

rivals that of the sculptor who strikes a mallet against marble and makes

a human body that seems alive.

Curiously enough, a fascination with just that kind of artistic alchemy

lies at the heart of Toku's life-long fascination with the briar

pipe. pipe.

|